Frederick Brown’s journey through art: Passage across form and passing on legacy

UPDATE: The subject of this story, artist Frederick Brown, passed away in the spring of 2012.

An Omaha cultural venue that has never enjoyed the attendance it deserves is the Loves Jazz & Arts Center. Then again, poor marketing efforts by the center help explain why so few venture to this diamond in the rough resource. The fact it’s located in a perceived high-risk, little-to-see-there area doesn’t help, but without the promotional initiative to drive people in numbers there it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy of folks avoiding the area like the plague. All of which is a shame because the center’s programming, while lacking full professional follow-through, has a lot to offer. An example of some very cool LJAC programs from a few years ago were workshops that noted artist Frederick Brown conducted there in conjunction with an exhibition of his work at Joslyn Art Museum. Some of Brown’s paintings of jazz and blues legends ended up on display at the center. I interviewed Brown during his Omaha visit and I think I managed capturing in print his spirit. The story originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com).

Frederick Brown’s journey through art: Passage across form and passing on legacy

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Leading contemporary American artist Frederick Brown offered a glimpse inside the ultra-cool, super-sophisticated New York salon and studio scene during a June visit to Omaha in conjunction with his current exhibition at Joslyn Art Museum. Showing through September 4, Portraits of Music I Love is a selection of Brown’s huge, ever expanding body of work devoted to jazz and blues artists under whose influence he came of age in the American avant garde movement of the 1960s and ‘70s.

The Georgia-born Brown was raised in Chicago, where he was steeped in the Delta Blues tradition that seminal figures like Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Dixon and Jimmy Reed, neighbors and friends, brought from the South. He grew up with Anthony Braxton. Later, in New York, he fell under the spell of jazz masters Ornette Coleman and Chet Baker. His intimate circle also encompassed the who’s-who of post-modern American painters, including his mentor, Willem deKooning. It was in this rarefied atmosphere of appreciation and collaboration Brown blossomed. He observed. He absorbed. He shared. The only condition for hanging with this heady crew, he said, was to “be unique — to bring something to the table.”

“At that time one of the nice things about living in an artist’s community like SoHo was that you had these people all around you who were at the top of their game and of the avant garde scene and of the aesthetic thing. I didn’t have to invent the wheel. The standard was set. Plus, right in front of me, I saw the work ethic. You could go to their studio or they could come to yours, and you could partake in whatever you wanted to partake in and discuss aesthetics at the highest level. You had all this kind of wisdom, information, feedback and back-and-forth,” he said.

Given all the time he’s spent with musicians, it’s perhaps inevitable Brown speaks in the idiom of a jazzman. That is to say he patters away in a hip, improvisational riff that sings with the eloquence of his thoughts, the musicality of his language and the richness of his associations, stringing words and ideas together like notes.

New York was the start of his being consumed with making it as an artist. “Total immersion. 24/7. Total commitment. Either I make it or die. A total spartan kind of situation,” he said, adding the artists befriending him “accepted and encouraged me.” Art is not only his inspiration but a legacy he must carry on. A set of musicians he was tight with, including Magic Sam and Earl Hooker, made him pledge long ago that after they were gone he’d preserve their heritage through his work. Then, after emerging as a bright new force in New York, his chronically troubled tonsils grew infected, but Brown had neither the insurance nor the cash to pay for an operation. He was resigned to dying when an anonymous benefactor stepped forward to foot the bill. It was 20 years before he learned his musician friends had ponied up to save his life. Ever since then, he’s felt a debt to further the art of jazz. His paintings at Joslyn represent a fraction of the music portraits he’s done as the fulfillment of that “promise.” At his 30,000-square foot studio in Carefree, Arizona he’s working on a 450-work National Portrait Gallery-curated series of jazz icons that will tour the world under the aegis of the U.S. State Department.

Jazz and blues artist Frederick J. Brown displays his painting “Stagger Lee,” in Kansas City, Mo.

Architecture was Brown’s first field, but when painting began speaking to him more deeply, he chose the life of an artist. He hit the ground running upon his 1970 arrival in New York, where he was immediately embraced for his talent, intellect and curiosity and for the fluidity of his technique and the originality of his vision.

“I’ve always had an innate ability to look at something or hear something and then do it. I could always paint in every style. If styles are languages, then I’m fluent in all of them. I never felt like any were above me or below me,” he said.

In amazingly short order, his work was exhibited in the Whitney Biennial, the Marlboro Gallery and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

He first made his mark in the realm of abstract expressionism, but always looking to stay “10 years ahead of the curve,” he changed directions to more figurative work and is often credited with helping bring back the figure in contemporary art. The small selection of his paintings at Joslyn are expressionistic figurative portraits that employ iridescent colors and bold brush strokes to evoke the singular essence and creative spark of such artists as Count Basie, Coleman Hawkins, Billy Holiday, Billy Eckstine, Bessie Smith, Dinah Washington and the late Ray Charles.

The prolific and versatile Brown is that rare artist with the ability to produce at the highest level while churning out a prodigious volume of pieces in quick succession. He’s tackled ambitious series’, massive single works, “mosaics” that fill entire rooms and themes ranging from the history of art to the Assumption of Mary. Still indefatigble at age 60, he can paint for hours without a break, as he did 13 hours straight during celebrated tours of China in the late ‘80s, and complete a fully realized work in the span of a musical cut or joint, something he’s done on countless occasions at rehearsals and recording sessions with musicians. Hanging with “the cats” at those jams, Brown does his thing and paints while they do their thing and play. Together, in harmony, each gives expression to the other.

“When you have people expressing, live, their spirit — in music, dance, poetry — these elements are cross pollinating the whole environment and gives the place another spirit and vibe and rhythm, too,” he said. “I’ve always painted very quickly. I can paint in the same rhythm and motion as the music. In fact, I can do one painting while they do one tune. So, every day doing that, doing that, for like 15 years — 30-40 paintings a day — every day, every day for all those years, you get to a certain level where it’s just like natural and you forget that it’s anything special.”

His experiences with performing and visual artists have prompted him to explore the mysteries of capturing music on canvas via color. “To hear Ed Blackwell play, it sounded like it was raining on the drums,” he said. “So, how do you translate that into color?” To get it right, Brown embarked on a study of color theories, harmonies and contrasts. “It’s like what color do you put next to another color to make that color brightest? It’s the same kind of thing you have in music. They’re all just notes. It made me have to think about this, where before it was just instinctual. Once I got it down, I didn’t have to think about it. It became subliminal again. And then I was just reacting to the sounds…and seeing the music.”

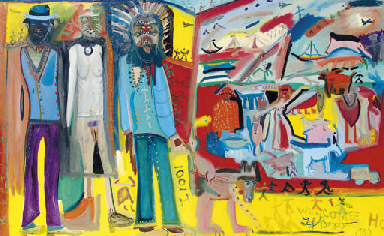

Welcome Home by Frederick Brown

In a series of cooperative workshops Brown conducted at the new Loves Jazz & Arts Center on North 24th Street, he simulated the fertile environs of the haute couture salons and loft studios he’s so familiar with. As his workshop students applied brush to canvas, bongo players beat out a driving rhythm, life models struck dance poses and Brown, turned out smartly in suit and shades, navigated the room, stopping at each easel to offer insight and encouragement to the students, who included some of Omaha’s best known artists. It was a sensual, visceral experience.

Brown’s painted this way for decades, using music as a channel for summoning his muse. “I always have music when I’m painting. I listen to a whole spectrum of music.” It’s about setting a mood for ushering in the shamanistic spirit he feels he possesses. Art as communion. “It’s like doing a jazz solo. You’re in that stream. It’s like a total zone you’re in and it just happens. You’re not conscious of it. In one sense my painting is like automatic writing,” he said. “No one can reproduce it, either.” It’s how he goes about painting his portraits of singers or musicians.

“When I’m doing this stuff I have their music playing or I have a photograph of them out,” he said. “Their spirit has to agree to come into that painting. In essence, I provide a painterly body for their spirit to inhabit. I’m a vehicle or a conduit for this information to pass through. Until the painting has a soul or a spirit, then it’s just paint on canvas. I just work on it until their spirit is satisfied,” he said. “You have to get in this like protective, almost out-of-body experience. With some people, like Johnny Hodges, you can express everything about them very quickly and simply. Others, like (Thelonious) Monk, are more complex. But sometimes you can catch the most complex situation in the fewest strokes.

“People always say, How do you know when you’re finished? Because it won’t allow you to touch it. The thing is complete. It doesn’t need any more brush strokes.”

Brown made his Omaha workshops a vehicle for exposing participants to new “possibilities” — “pushing” artists beyond self-imposed “limits” by having them, for example, create 24 paintings in a single night. He also made the classes a means for imbuing the Loves Center, whose mission is to be a venue where all the arts meet, with a synergistic “energy” open to all forms of expression. “What it comes down to is one person expressing themselves in a certain way and being inspired by different mediums. It’s getting more people involved. It’s opening minds, just like Ornette and them did for me.”

Related articles

- When Jazz Married Art (doublelattebooks.wordpress.com)

- Arno Lucas, Serious Sidekick (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Yolonda Ross Takes It to the Limit (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Enchantress “LadyMac” Gets Down (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Camille Metoyer Moten, A Singer for All Seasons (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Frederick J. Brown, Painter of Musicians, Dies at 67 (nytimes.com)

- Eddith Buis, A Life Immersed in Art (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- For Love of Art and Cinema, Danny Lee Ladely Follows His Muse (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Jazz-Plena Fusion Artist Miguel Zenon Bridges Worlds of Music (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Peter Buffett Completes the Circle of Life Furthering the Legacy of Kent Bellows (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

I like the valuable information you supply to your articles.

I will bookmark your blog and test once more here regularly.

I am somewhat certain I’ll be informed lots of new stuff proper right here! Best of luck for the next!

LikeLike

Fredrick brown is an exceptional artist….happy owner of Robinhood

LikeLike

This is a wonderful write-up, so glad to see it reposted. I work with the Frederick J. Brown Collection and would love to connect with the happy owner of Robin Hood as well as any others with an interest in Frederick Brown’s work.

LikeLike